Goscript Internals II: The Runtime, Part A

Ingredients

The previous overview promised a "relatively original wheel", however the runtime is in fact more like a cocktail. Most of the ingredients are from Lua, Python Go and Rust.

-

The VM and instruction design is inspired by Lua. Like Lua, Goscript has a register-based VM, and it also uses "upvalue" to support closure.

-

The memory management and GC is similar to Python's. Goscript uses reference counting and circular reference detection to reclaim memory.

-

To behave exactly like the official version of Go, the data structures have to simulate how they work originally, things like Interface and Slice.

-

To implement async features like goroutine and channel, async-await and channel from Rust ecosystem are used.

Instruction set

Instructions (instruction.rs) can be divided into five categories:

-

Accessing. Copy between registers; access array/slice/map/upvalue/pointers.

-

Operation. Things like plus and minus, things denoted by operators.

-

Function call and return.

-

Jump.

-

Built-in functions. Both the implicitly used ones like BIND_METHOD, and the explicit ones like NEW and COPY.

Architecture of the VM

Let's take a look again at the previous example:

package main

func main() {

assert(addN(42,69) == mul(42, 69))

}

func addN(m, n int) int {

total := 0

for i :=0; i < n; i++ {

total += m

}

return total

}

func mul(m, n int) int {

return m * n

}

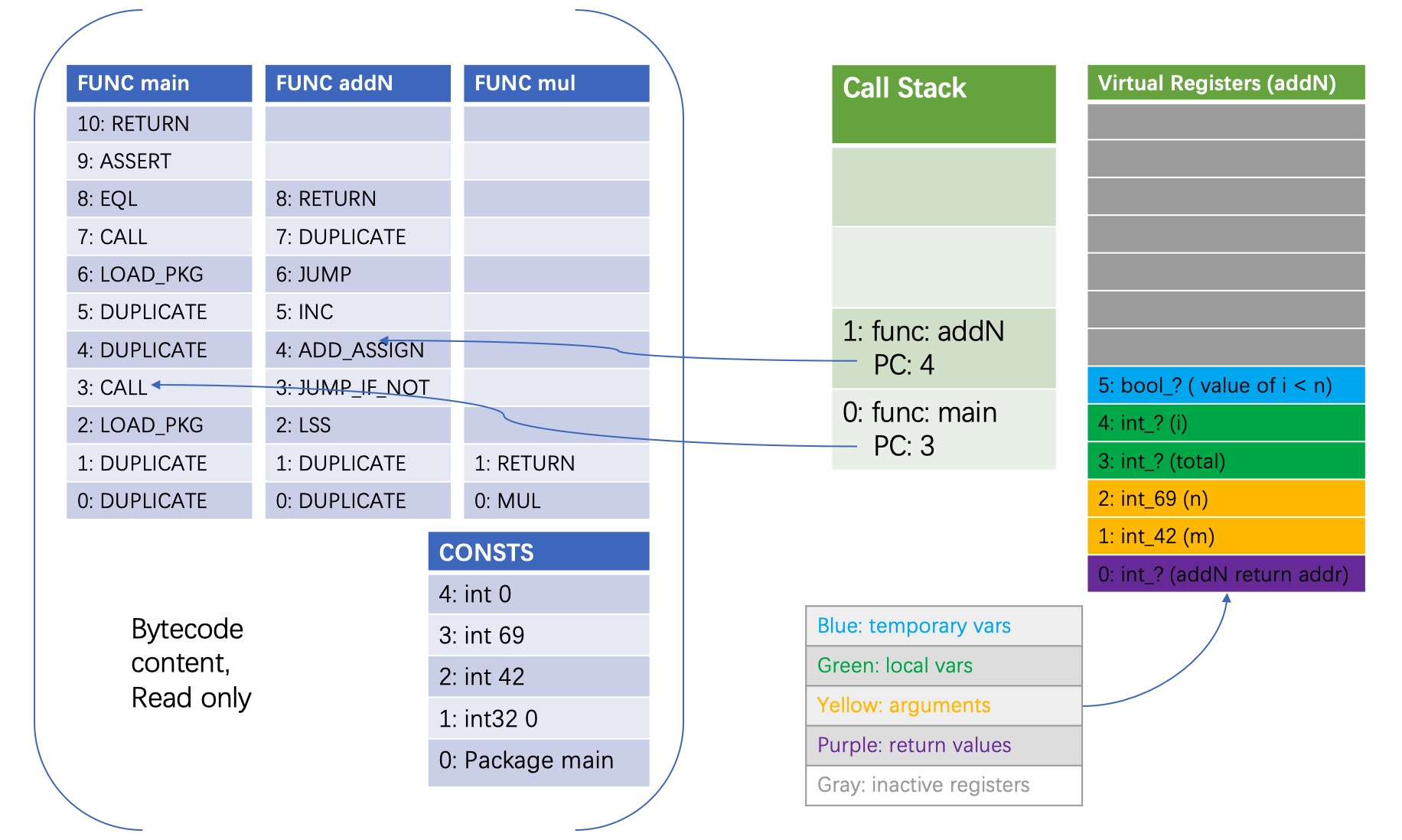

Below is a snapshot of the example running on the VM:

This diagram shows what's in the memory when

This diagram shows what's in the memory when total += m of addN is being processed. On the left side is the loaded bytecode including the instructions and consts, which are read only.

The right side is more interesting. You should be no stranger to call stack, when main and addN get called, call frames generated for them and pushed to call stack, they'll be popped out when the functions return. Call frame is used to record information about the running function including the most obvious one: PC.

Last but not least, the virtual registers. As the diagram shows, when a function is called, a set of virtual registers are allocated for it in the following order: return value, arguments, local vars, temporary vars. Registers and consts are the only two places where instructions can read from, and registers are the only place to write to.

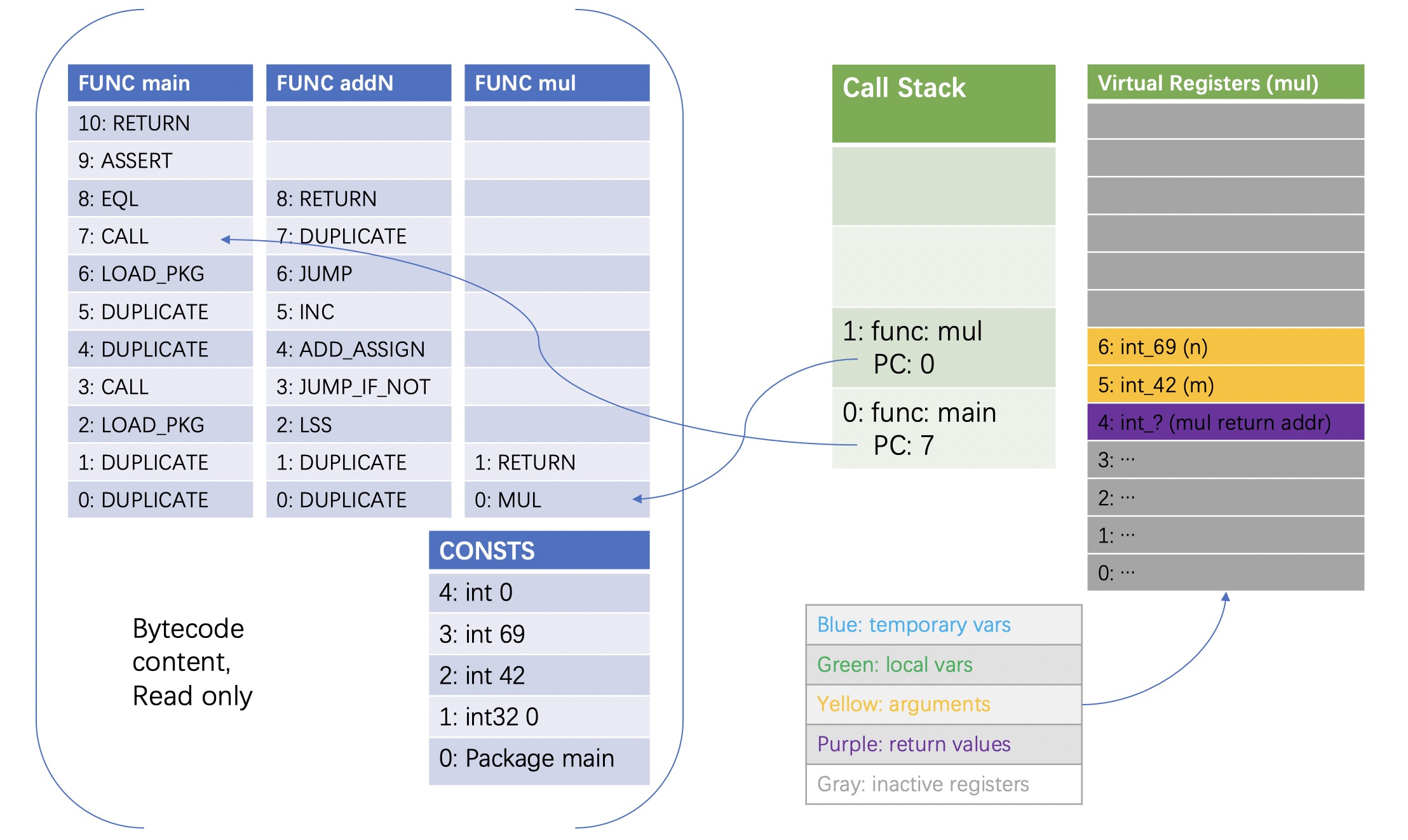

For every step, the processing loop does the following: Fetch the instruction that the PC of the active call frame on the top of the call stack points to, and process it. Then the PC is either increased by 1, or modified to perform a jump. If the instruction is a CALL / RETURN, the active call frame is changed.

This is when m * n of mul is being processed after addN returned and mul is called:

Upvalue

"The combination of lexical scoping with first-class functions creates a well-known difficulty for accessing outer local variables". -- 《The Implementation of Lua 5.0》. Goscript steals the solution from Lua as it faces the same problem.

Here is an example:

package main

import "fmt"

// Returns a function that add 'up' to the input 'i'

func makeAdd(up int) func(int) int {

return func(i int) int {

return up + i

}

}

func main() {

add42 := makeAdd(42)

c := add42(1)

fmt.Println(c)

}

Let's focus on add42 := makeAdd(42), typically, when makeAdd returns, the argument 42 is released, but in our case, it cannot be released as it's still referenced by add42. Lua solve this by using a pointer that points to the up value , hence the name. In the example, add42 holds an upvalue pointing to 42.

The design of upvalue is relatively simple. When makeAdd is not returned yet, the upvalue is just the address of up in the virtual registers, so both the outer and the inner function can access it from the register. When makeAdd returns, the value of up get copied to the heap, and the upvalue becomes a real pointer pointing to the heap value.

The upvalue is open when up is still in the register, the upvalue is closed when up is in the heap.

Pointer

It turns out upvalue can also be used elsewhere: pointers.

There is no VM-based language supports pointers as far as I know, but Goscript has to. Luckily there are limitations for the use of pointers according to the Go specs. Simply put, pointers can only be created to point to certain things, for Goscript, they are:

- local variable

- package member

- slice member

- struct field

In Goscript, package, slice and struct are all stored in the heap, and we have real pointers that point to them, so a combination of (pointer, member_index) is sufficient to represent those three. For local variable, a pointer to it behaves exactly the same as an upvalue, so it is implemented as an upvalue.

Goroutine

As the most iconic feature of Go, goroutine may seem complicated to implement, surprisingly, it's not. Before look into the details of Goscript's coroutine, let's talk about coroutines in general.

In terms of where you can yield, there are:

- Stackful coroutines, meaning they can yield and later resume freely

- Stackless coroutines, meaning they can only yield back to the parent coroutine and later get resumed by the parent coroutine.

In terms of how coroutines cooperate with each other, there are:

-

Preemptive coroutines, meaning busy coroutines get suspended by the scheduler once in a while to give other coroutines a chance.

-

Cooperative coroutines, meaning coroutines runs indefinitely until they explicitly yield.

Go has a stackful preemptive coroutine system, which is also the most user friendly.

In Goscript, for every goroutine a processing loop is launched, which is an async function, and an await can happen at any point inside the loop. Async Rust functions can also be called inside the loop via Goscript FFI.

The loop yields after a certain amount of instructions are processed, so that the users don't need to call yield explicitly, making the whole system preemptive.

With the help of Rust's async-await, we have a simple solution behind a powerful feature. It's easier to understand from a different perspective: a goroutine is just a Rust future.

Coming up next

Thera are a lot more Go features to cover in the runtime, I'm planning to finish them in the next installment.