Goscript Internals I: Overview

Introduction

Goscript is a VM-based Golang implementation written in Rust. Goscript Internals will be a series of articles explaining Goscript's design. The intended audience are any experienced programmers who are interested in how Goscript works--or, more generally--how a compiler/ a scripting language/ a Go implementation works. You don't need to have a background in compilers, Go or Rust but it does help if you do. This first article is a brief introduction of how a typed scripting language works, which may be boring to experts.

Before we dive in, let's make a table of all the sub-projects:

| Project | Description | Language | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parser | turns source into AST | Rust | ported from Official Go |

| Type Checker | type deduction and more | Rust | ported from Official Go |

| Codegen | turns AST into bytecode | Rust | original work |

| VM | runs bytecode | Rust | original work |

| Engine | wrapper and native library | Rust | original work |

| Std | Standard library | Go | adapted from Go |

Let's get a big picture of how things work by looking into what happens with this simple program, when Goscript runs it:

package main

var a = 1

func main() {

b := 2

c := a + b

assert(c == 3) // built-in function

}

The parser

The parser read the source code and turns it into an AST (Abstract Syntax Tree)

- A hand-written tokenizer (scanner.rs) turns the source code to a list of tokens like this:

`

package, main, var, a, EQL, 1, ...

`

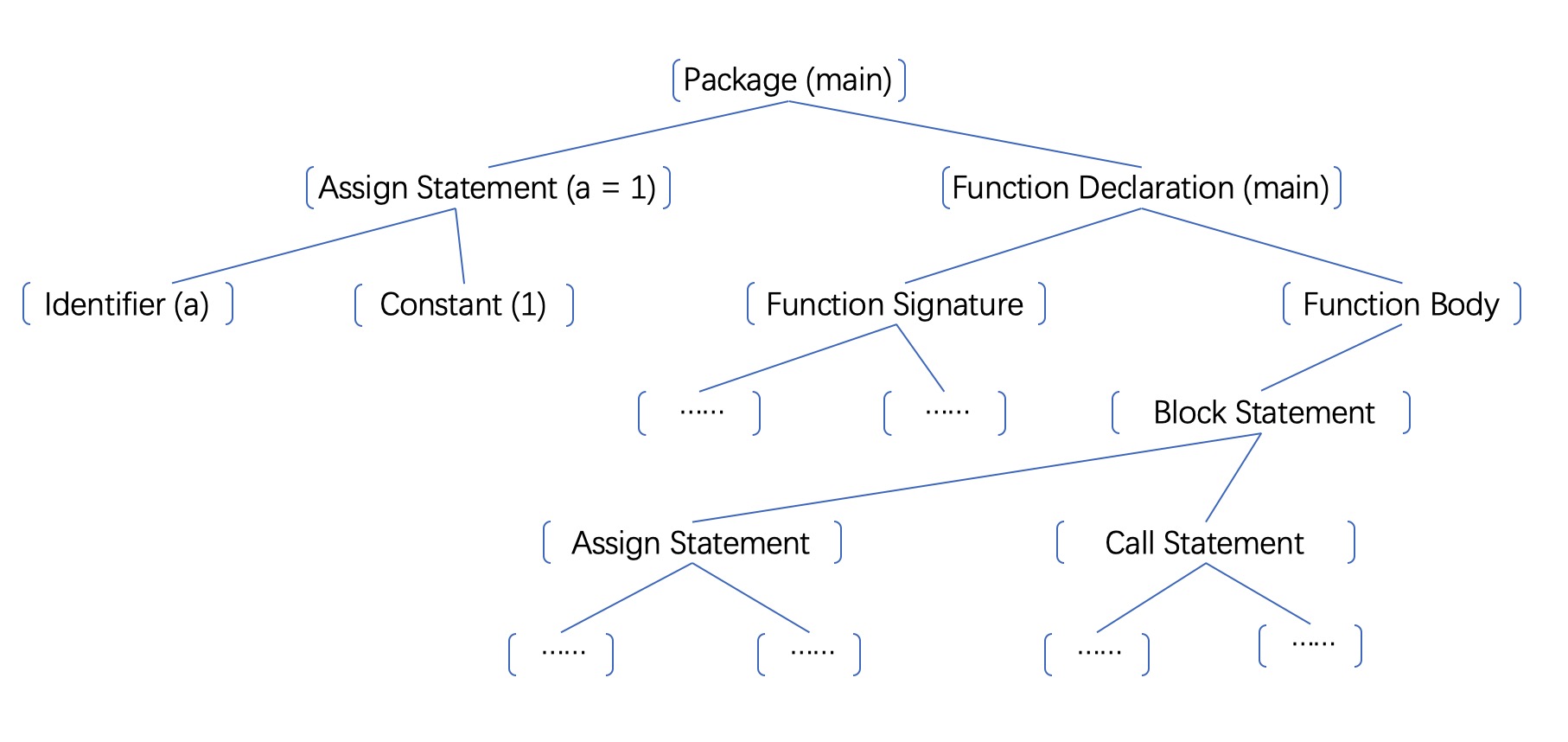

- A hand-written recursive descent parser (parser.rs) turns the list of tokens into a tree. This step might look magical, but in fact quite intuitive, it's just a recursive program, that try to build nodes of different types of statements and expressions, by matching the tokens it sees and the tokens it expects. The tree definition can be found here (ast.rs). The AST of the above program would be something like this:

The type checker

The main task of the type checker is type deduction, which means figuring out the exact types of variables, structs, functions etc. to provide type information for code generator and to catch more syntax errors. It does so by traversing the AST and enforcing the rules defined in the language specs. You can take a quick look at expr.rs and stmt.rs to get a general idea of how it works.

In the case of the above example, it deduces that the types of a, b, a + b and c are all int, and the type of c == 3 is bool. it also checks that assert does accept one and only one bool argument.

The type checker is the most complex part of the whole project, there is an Go official document talking about it in detail. In addition to type deduction, it does identifier resolution, constant evaluation, and the insignificant looking init order computation.

The result of a type checking pass is a syntax error free AST, and a very rich database of type info about the AST, which will be used for bytecode generation.

The code generator

The code generator traverses the AST again to generate runtime objects containing the bytecode. For the example above, it generates objects that logically look like this:

`

- Package Object (main)

- Package member variable (a)

- Package member function (constructor)

- bytecode:

// copy constant10 to register0, which is where "a" is

DUPLICATE |0 |-10

RETURN

- Package member variable (main)

- bytecode:

// copy constant7 to register0, which is where "b" is

DUPLICATE |0 |-7

// load from package8's 0th member, which is "a", to register2

LOAD_PKG |2 |-8 |0

// register1 = register2 + register0

ADD |1 |2 |0

// register2 = (register1 == constant9)

EQL |2 |1 |-9

// crash if register2 != true

ASSERT |...|2

RETURN

`

As you can see, Goscript abandoned the original stack-based VM in favor of a register-based one. Stack-based VM is intuitive to design, but less efficient. With a stack-based VM, the above ADD would probably need three extra instructions -- two "PUSH" and one "POP" -- to do the same job.

In essence, code generator is just a translator, which translates a tree into a one dimension array, so that for the VM, instead of traversing a tree, which is totally doable but would be much less efficient, it only needs to deal with instructions on a virtual tape one by one, plus jumping back and force. The main part of the code is codegen.rs.

The virtual machine

As stated above, the VM is just a big loop (vm.rs) that processes instructions until they run out. All the instructions can be divided into three categories:

`

- The normal ones:

ADD, SUB, EQL, LOAD_ARRAY ...

- The ones lead to jumping:

JUMP, JUMP_IF ...

- The ones lead to jumping between functions:

CALL, RETURN

`

Let's write a slightly more complex program as an example:

package main

func main() {

assert(addN(42,69) == mul(42, 69))

}

func addN(m, n int) int {

total := 0

for i :=0; i < n; i++ {

total += m

}

return total

}

func mul(m, n int) int {

return m * n

}

Below is the generated code, the instructions are numbered to make it easier to refer to:

`

main:

1 DUPLICATE |1 |-3 |... |... |...,

2 DUPLICATE |2 |-4 |... |... |...,

3 LOAD_PKG |3 |-1 |1 |... |...,

4 CALL |3 |0 |... |FlagA |...,

5 DUPLICATE |5 |-3 |... |... |...,

6 DUPLICATE |6 |-4 |... |... |...,

7 LOAD_PKG |7 |-1 |2 |... |...,

8 CALL |7 |4 |... |FlagA |...,

9 EQL |8 |0 |4 |Int |Int,

10 ASSERT |... |8 |... |... |...,

11 RETURN |... |... |... |FlagA |...,

addN:

12 DUPLICATE |3 |-5 |... |... |...,

13 DUPLICATE |4 |-5 |... |... |...,

14 LSS |5 |4 |2 |Int |...,

15 JUMP_IF_NOT |3 |5 |... |... |...,

16 ADD_ASSIGN |3 |1 |... |Int |...,

17 INC |4 |... |... |Int |...,

18 JUMP |-5 |... |... |... |...,

19 DUPLICATE |0 |3 |... |... |...,

20 RETURN |... |... |... |FlagA |...,

mul:

21 MUL |0 |1 |2 |Int |...,

22 RETURN |... |... |... |FlagA |...,

`

This is what happens when the VM execute the code:

`

1: Copy 42 to register1 as addN's argument

2: Copy 69 to register2 as addN's argument

3: Load "addN" to register3

4: Call "addN", jump to instructions in "addN"

12: Initialize "total" as 0

13: Initialize "i" as 0

14: Compare register4("i") and register2("n") to see if i < n, and put the result in register5

15: If register5 is not TRUE, jump to 19

16: total += m

17: i++

18: Jump back to 14

14: ...

... ...

14: ...

15: Jump to 19

19: Copy register3("total") to register0(return value)

20: return, jump back to "main"

5: Copy 42 to register5 as mul's argument

6: Copy 69 to register6 as mul's argument

7: Load "mul" to register7

8: Call "mul", jump to instructions in "mul"

22: register0(return value) = register1(argument1) * register2(argument2)

23: return, jump back to "main"

9: Compare register0 and register4 to see if they are equal, and put the result in register8

10: crash if register8 != true

11: return, jump out of main and exit the program

`

Coming up next

So far, there is almost nothing specifically about Goscript, pretty much the same thing happens in Python, Lua or even Java, though there are a few differences: Python or Lua doesn't have a type checker, and Java has a much more complicated VM.

The next article will be a deep-dive into Goscript's VM, to explain how various of Go features are implemented in a simple VM, which, unlike to other parts of the project, is a relatively original wheel that got invented.